Falling Grace - Directed Practice

Falling Grace, by Steve Swallow, is one of my favorite tunes. It’s an odd one, for sure. Despite traversing around 8 key centers (depending how you count) and having a 24 bar form (divided into 14 plus 10), it’s very listenable, logical, and widely played. Especially at Berklee, where it felt like every jazz performance student knew it well. There’s a plausible explanation for that - when the Real Book was being put together by Berklee students back in the 70s, Swallow contributed a few of his tunes, not exactly standards, to the effort.

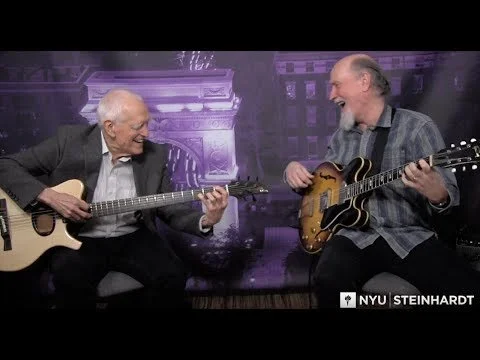

The Real Book was supposed to reflect practical tunes that people played, and eventually became influential in its own right as the first compendium of standard lead sheets most students encounter, shaping their initial repertoire. I think Falling Grace benefited from this. In the video below, Swallow talks about the origins of the Real Book starting at minute 22:

He also talks about wanting to make his tunes available for everyone to play, one of the reasons he allowed them in the Real Book in the first place. True to form, you can check out (all) his lead sheets on his website. The lead sheets above come from the website and the Real Book - it is interesting to note the differences. On to the tune and a concept I like to call “directed practice.”

One of the first things to do to get acquainted with this piece is to break it up into logical sections. Click “Expand” below to see how I think about it.

-

Bars 1-4: Ab major - a I chord of sorts - followed by a quick V7 of G minor, landing on G minor. These tonalities may “look” distant, but when you break it down, the difference between Ab Lydian (the melody makes this clear) and G natural minor is one note - Ab vs. A. You’ll find yourself using these two notes to pivot, alongside your “V7 of minor” material, such as emphasizing the F# leading to G.

Bars 5-6: Eb major via a quick II-V, then tonicizing G minor again. If you think about it, these two bars are a compressed version of the first 4, although you’re not landing on G minor until bar 7. Practice moving from Eb major to V of G minor, and again you’ll notice the Ab to A natural pivot point. Why not Eb lydian? Because it’s a II-V in Eb (in which Ab is a very important note), and the I chord, Eb, happens very quickly. Emphasize the A rather than Ab over that Eb chord and you’ll lose the contrast as you move to G minor.

Bars 7-8: a breather. You land on G minor, which becomes the II chord in a long II-V to F major. I’d note that in Steve’s lead sheet, he calls the C in bar 8 as Cmaj7. Practically, this part just sounds like a V chord to me, moving to F major, so I treat it as such, and play Bb rather than B. Maybe this is wrong, but that’s what I hear listening to others as well (such as approx 2:15 here), and what you’d conclude looking at the Real Book chart, where I’m guessing most musicians learned this tune.

Bars 9-12: the same thing as the first 4 bars, just starting in F. The notes F to F# function as the pivot point as you move from F major to E minor via a long II-V. In this version, you start moving to E minor a bit earlier as the F#-7b5 comes in the second bar, but otherwise, it’s analogous.

Bars 13-14: another breather. Sounds almost like a “tag.” I’m thinking G major, easy to get to as it’s the relative major of E minor. Just gravitate to the “major” part of the scale.

Bars 15-18: new section. Looks like new material, but it is very similar to the “major to minor a half step lower” concept he has written twice before in the tune. Measure by measure:

15: First, I make the observation that C minor in this context has the same notes as Eb major. You can think in Eb here and the bass will take care of the C root. It is all “tonic” anyway.

16: From “Eb/C,” I make the second observation that C#dim7 is another way of writing A7b9, which is V7 of D minor. The melody also has an A natural in it, and this interpretation definitely sounds plausible. (I could also see someone thinking in Bb major here, with the C#dim7 functioning as a bIII diminished or #IV diminished leading to the I chord. It all sounds the same to me.)

17: Here I make the THIRD observation that D minor and Bb major are closely related, and I think in D natural minor. So from bar 16-17, it’s just A7 to D minor for me. Now it should be clear that my interpretation of bars 15-17 - Eb major —> A7 —> D minor - is the exact same thing as what’s happened before in this tune starting in Eb, rather than Ab and F.

18: Back to Eb major. Sounds like a IV chord.

Bars 19-24: this section, as well as the prior one, can be thought of generally in Bb major. We start with a II-V in D minor (II-V of III), familiar material since we’re coming from Eb major. This is the fourth instance of “major to minor a half step lower.” When you land on D minor in bar 21, there is a descending sequence getting you to C-7, which functions as the II in a quick II-V to Bb. This “falling” motion happens in the Real Book, and is the way everyone plays it, but not in the Steve Swallow lead sheet. You can think of it as III-VI-II-V, or III-bIII-II-V - I think both sound good. Then you get a nice breather with a Bb major tonic and its subdominant, Eb major, before returning to the top of the form.

Now that the theory is out of the way, it’s time to practice playing the tune. ONE of many things I like to include in my practice routine is what I call “directed practice,” or adding forced direction to the lines you are playing. You take a solo, and within it, you section off periods of time where you will go in a specific direction, like “up” or “down” or “static.” These sections can be measures long, the entire form, multiple choruses, the entire solo, etc. But you force yourself to add some direction over a period of time.

Here’s a short example, where I am going “up” twice over the span of a chorus. First the melody, then one chorus of solo: